Happy New Year, dear bakers! I hope you had a festive and joyous holiday season with friends and family. I brought you some holiday gift ideas, recipes, and baking advice over on the channel this November and December. If you haven’t had a chance to watch them, head over to YouTube and hopefully they’ll give you some ideas for next Christmas!

Now that the holidays are behind us, I’ll be turning my focus to the full series I filmed in Budapest and Vienna last October. I wanted to share a bit of background on Hungarian cuisine to help set the stage for what’s coming.

Be sure to read to the end, where I share a new recipe, plus something I’m really excited about—my first eBook!

For hundreds of years Hungary was referred to as the country of romance, wine and gypsy music, but perhaps the most fitting title should be: the land of ten million pastry lovers.

Hungary After 1848: A Turning Point at the Table

This month, we are stepping into a pivotal moment in the story of Hungary’s cuisine, one that reshaped not just politics and society, but the way people cooked, ate, and gathered around the Hungarian table. After the failed 1848–1849 revolution, the country entered a period of rapid transformation. Feudal systems weakened, agriculture and industry modernized, and scientific approaches to farming, preservation, and production began to take hold. These changes opened Hungary to international trade and ideas, setting the stage for growth and innovation that would define the second half of the nineteenth century, especially after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867.

Coronation of Emperor Franz Joseph and Empress Elisabeth of Austria as King and Queen of Hungary, on June 8th, 1867, in Buda, Capital of Hungary

From Private Homes to Public Life

With this new era came a flourishing of urban life, hospitality, and culinary ambition. Grand hotels, cafés, and restaurants appeared in Budapest and across the country, designed to rival those of Vienna, Paris, and London. Celebrated chefs, restaurateurs, and musicians helped create spaces where food, culture, and social life blended seamlessly. Cookbooks circulated more widely, menus grew more refined, and the standards once reserved for aristocratic homes moved into public dining rooms. This was the moment when Hungarian cuisine, including its baking traditions, began to take on the polished, confident identity that would earn international admiration and lasting influence.

Fortepan / Budapest Metropolitan Archives / Photographs by György Klösz

At the same time, the coffeehouse emerged as one of the most important public institutions in Hungarian life. Budapest’s cafés were not casual stops, but places where writers, journalists, musicians, actors, and political thinkers spent entire days. Newspapers were read, edited, and debated at café tables. Plays, poems, essays, and musical ideas took shape alongside cups of coffee. For many, the coffeehouse functioned as a second home, an office, and a forum, deeply intertwined with the cultural and political life of the city.

Fortepan / Kurutz Márton

Many patrons structured their entire day around the coffeehouse, arriving in the morning to read newspapers, returning in the afternoon for coffee, and gathering again in the evening for conversation, cards, or music. Although coffeehouses began by serving little more than coffee and tobacco, their menus gradually expanded to include chocolate, pastries, and light meals. Over time, this evolution blurred the boundary between café and restaurant and anchored the coffeehouse as a daily institution rather than an occasional indulgence.

Fortepan

From Village Kitchens to Legendary Pastry Houses

Hungarian pastry culture grew from a mix of everyday cooks, traveling artisans, and literary curiosity. Writers and journalists collected recipes directly from villages and countryside kitchens, preserving techniques that had been passed down for generations. At the same time, Hungary developed a reputation for deep enthusiasm for pastries, with sweets playing an unusually prominent role in daily life. Influences came from many directions. French tortes, Austrian home-style cakes, Italian chocolate making, and Near Eastern honeyed sweets all found a place in Hungarian kitchens. Pastry guilds existed as early as the Middle Ages, and by the eighteenth century, dedicated pastry shops had begun to appear, shaping a professional baking tradition grounded in skill, repetition, and cultural memory.

Gerbeaud / Fortepan / Budapest Metropolitan Archives

These pastry shops quickly became places of legend. One of the most famous, Ruszwurm Cukrászda in Buda, welcomed aristocrats, poets, and everyday citizens alike and became a fixture of the city’s social life. Like the coffeehouses, pastry shops served as gathering places for conversation and exchange, though with a focus on sweets, display, and ritual.

Ruszwurm / Fortepan / Szöllősy Kálmán

Stories accumulated in these rooms, from political discussion during revolutionary periods to romantic scandals that inspired new desserts. The tale of the gypsy violinist Rigó Jancsi and his affair with a runaway aristocrat captured the public imagination and gave Hungary one of its enduring chocolate cakes. In Hungary, pastries were never just sweets. Over time, they became part of the country’s national identity and everyday cultural life.

Rigó Jancsi cake by Winnie135 / CC BY-SA 4.0

The New Era of Pastry

As Hungary entered its New Era at the turn of the nineteenth century, pastry making moved from tradition into true creative expression. Hungarian pastry chefs became known for invention, spectacle, and delight. New tortes appeared constantly, made with unexpected combinations and technical ambition. Whipped cream, once a novelty in Hungarian baking, became central to desserts, and bakers refined fillings, textures, and presentation with increasing confidence. Pastry shops were no longer just places to eat sweets. They became stages where new cakes were introduced, discussed, compared, and remembered.

Fortepan / Kotnyek Antal

Nowhere was this more visible than in Budapest’s great pastry houses. Shops like Gerbeaud and Ruszwurm set the standard for elegance, craft, and abundance. These spaces offered coffee and cake alongside elaborate displays of tortes and slices, inviting guests to linger, observe, and return. Like the city’s coffeehouses, pastry shops became refuges from daily life, places where conversation unfolded slowly and time was less rigid. Unlike restaurants, which followed stricter structures, pastry shops allowed for lingering and indulgence.

Millennium Exhibition: Gerbeaud's confectionery pavilion / Fortepan / Budapest Metropolitan Archives.

The People Behind the Cuisine

This period also produced towering figures who shaped Hungarian cuisine far beyond dessert. József Marchal brought French techniques into Hungarian kitchens with discipline and careful judgment, adapting it to local tastes rather than overwhelming them. His influence reached from royal coronation dinners to the training of future culinary leaders. Menus became more balanced, refined, and self-assured, proving that Hungarian food could stand confidently on the world stage without losing its character.

Portrait of József Marchal

Among the most celebrated figures of the era was József C. Dobos, a pastry chef who understood both innovation and restraint, knowing when to introduce something new and when to protect it. When he introduced the Dobos Torte in the late nineteenth century, it stood apart from existing cakes not for decoration, but for its engineering.

József C. Dobos

Designed at a time when refrigeration was limited, the cake was built to travel, keep well, and remain elegant under less-than-ideal conditions. Its thin sponge layers, carefully balanced buttercream, and sealed caramel top combined innovation with indulgence, allowing it to be shipped up the Danube and beyond.

Dobos protected the recipe for years to maintain its standard, then later released it publicly so its legacy could live on beyond his own lifetime. The result was a cake that became a national reference point and an international success, celebrated with anniversaries, parades, and lasting respect. This cake is so central to Hungarian national identity that you’ll even find it adorning Dobos’ own grave.

I went on the hunt for Dobos’ grave in Budapest and found it!

Then there was Károly Gundel, a rare figure whose influence reached restaurants, hotels, cookbooks, and generations of chefs. Guided by discipline, humility, and an unwavering sense of responsibility to guests, Gundel helped define modern Hungarian hospitality. His belief was simple and lasting. Food should bring pleasure, comfort, and a sense of being cared for.

Károly Gundel

The Gundel Restaurant, located near Budapest’s City Park and long associated with international visitors, state events, and formal dining, still operates today and remains one of the country’s most historically significant restaurants. His legacy lived on through his children, his students, and a national cuisine that valued both excellence and care.

Gundel Restaurant

The famous Gundel pancakes

By the time Hungary fully stepped into the New Era, its cuisine had absorbed centuries of influence while remaining unmistakably itself. From village baking traditions to imperial banquets, from coffeehouses that shaped literature and politics to pastry shops that anchored daily ritual, Hungarian food tells the story of a small country with an enduring devotion to food and hospitality. For pastry lovers especially, Hungary became a place where history, identity, and baking were always closely intertwined.

What Comes Next

Dobostorta at Centrál Grand Cafe, Budapest

In the coming weeks, I’ll be sharing a new video series filmed entirely in Budapest that brings this history into the present. Each episode centers on a pivotal dessert in Hungarian cuisine, exploring where it came from, how it was eaten, and why it mattered. I walk the city to trace each dessert’s story, taste it in a historic café or pastry shop, and then return home to my own kitchen to show you how to bake it yourself.

Coffee at New York Café, Budapest

The first episode focuses on the most famous dessert in Hungarian baking, the Dobos Torte. We’ll look at its history in Budapest, try it in a classic coffeehouse setting, and then break it down step-by-step so you can make it confidently at home.

Dobostorta to-go from Café Művész, Budapest

While I spent a lot of time in Budapest filming the showstopper desserts, I kept noticing the quieter, simpler bakes that appear all over Hungary, both in coffeehouses and on grandma’s table. These everyday recipes are just as much a part of Hungarian cuisine as the creations of pastry chefs.

That’s what led to a small project I’ve been working on:

my first e-book, coming out next week!

It focuses on the kinds of bakes you’d find in neighborhood bakeries or on a grandmother’s coffee table. The foods many people remember from childhood, like cherry cake after the summer harvest or a kifli buttered and eaten before school.

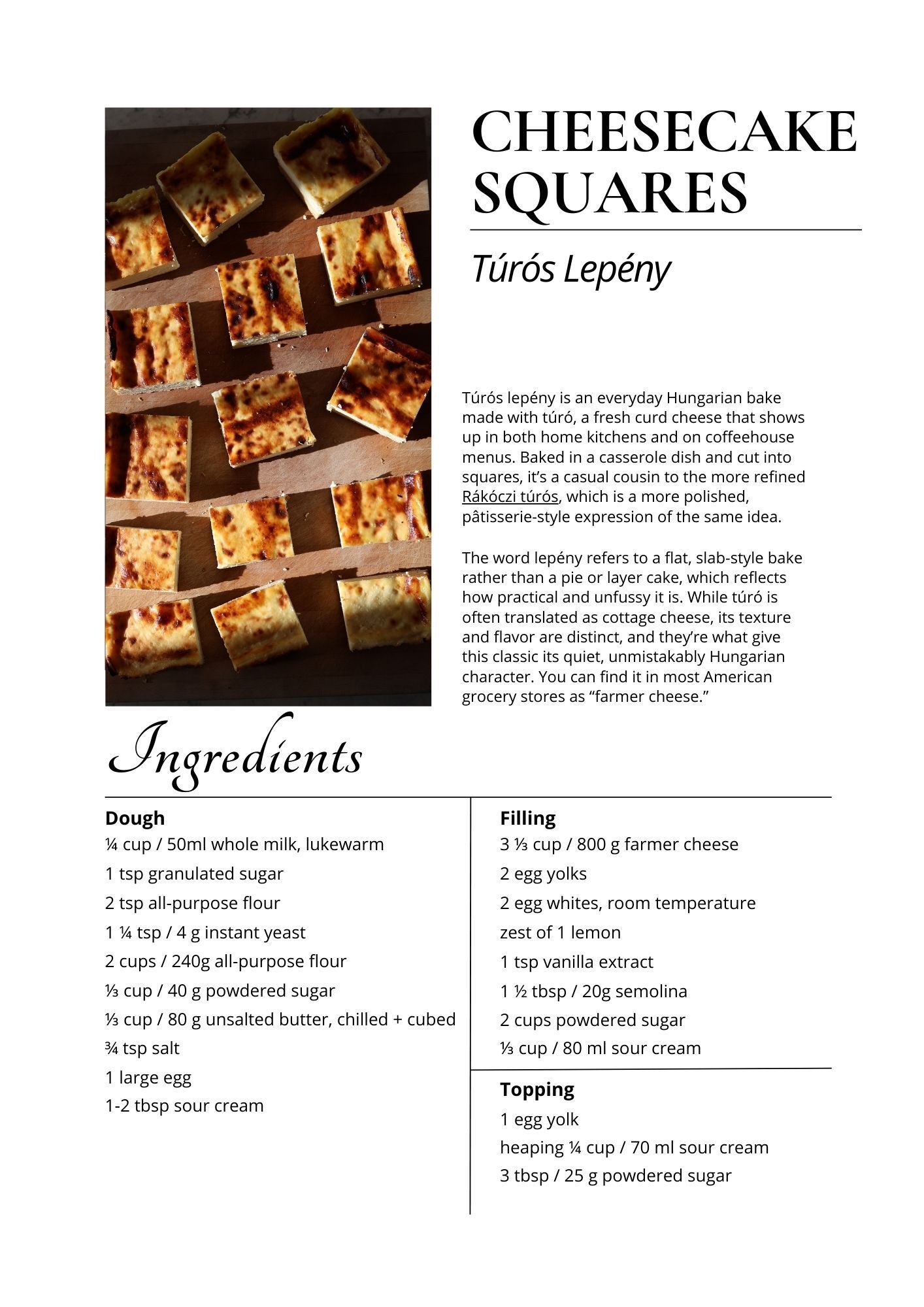

To give you a taste of what’s inside the book, I’m sharing one of the recipes here: cheesecake squares.

Cheesecake Squares / Túrós Lepény

A few months ago, I filmed a video on a Hungarian cheesecake called Rákóczi túrós. It’s a showstopper, with a shortcrust base, farmer cheese filling, and a lattice of meringue and apricot jam on top, and it appears on the menu of many coffeehouses.

The version I’m sharing today is much simpler. It has the same familiar flavors, but without the frills. This is an everyday cheesecake with a yeasted base and a straightforward farmer cheese filling. Sour cream, egg yolks, and sugar create a lightly caramelized topping.

Don’t let the yeasted dough intimidate you! There’s no rising time. You simply mix the ingredients, roll it out, and bake.

If you’re in the U.S., farmer cheese is available at many grocery stores under the Friendship brand. If you can’t find it, drained ricotta will work, though the flavor won’t be quite the same.

I hope you give this cheesecake a try the next time you’re looking for something simple to enjoy with friends over coffee. And keep an eye out for the email about the e-book next week!

Printable on Desktop

Printable Desktop

Until next time, happy baking!

Kristin