Belgium’s Sweet Legacy: Sugar, Waffles & More

Every month, I love to share with you not just recipes, but the rich cultural stories behind them. This time, we’re heading to Belgium, home of the Liège waffle, speculoos, pearl sugar, and so many sweet traditions. Behind these iconic flavors lies a fascinating history: the story of Antwerp as the Sugar Capital of Europe.

This is more than a tale of trade. It’s a saga of ships, wars, art, and innovation that stretches from medieval legends all the way to the brown sugars and pearl sugars that still sweeten Belgian kitchens today. So grab a warm drink, settle in, and let’s journey through time to see how sugar shaped a city, and how that legacy lives on in the bakes I’ll highlight this month. At the very end, I’ll give you a new recipe to add to your European baking repertoire.

…there is no better way to build identity than through culinary delights.

A City Born of Legend and Trade

View of Antwerp by Jan Wildens, 1500

The very name “Antwerp” is wrapped in legend. According to a medieval tale, a Roman soldier named Silvius Brabo saved the city from the giant Antigoon, who terrorized travelers by demanding tolls to cross the river Scheldt. Those who refused paid with their hands, Antigoon cut them off and threw them into the river. When Brabo defeated the giant, he too cut off Antigoon’s hand and hurled it into the Scheldt. The Dutch phrase hand werpen (“throwing a hand”) gave birth to “Antwerpen.”

Brabo throwing Antigoon’s hand into the river. Statue located in the Grote Markt, Antwerp.

This riverside city wasn’t just legendary. It was strategic. Antwerp sat on the river Scheldt, a waterway connecting it directly to the sea, and for centuries it thrived as a hub of trade and crafts. By the late Middle Ages, Bruges had begun to decline as its waterways silted up, while Antwerp rose as a crossroads for Europe’s wealthiest merchants.

Scaldis ("the Scheldt") and Antverpia ("Antwerp"), Abraham Janssens, 1609

The Rise of Sugar in Antwerp

Sugar first appeared in Antwerp records in the early 16th century, though by then it was already an established luxury in other parts of Europe. The earliest mention comes from 1508, when the sugar refiner Jan de Lijs is documented. By the 16th century, Antwerp had become the beating heart of Europe’s sugar economy, rivaling Venice.

By 1560, the city counted at least twenty-five refineries, with some sources noting there may have been even more. These refineries were often tucked into the city center, complete with warehouse space to store the heavy sugar loaves before export. Antwerp’s harbor brought in raw cane sugar from Portuguese and Spanish colonies in the Atlantic, processed it, and shipped it out again across Europe.

Saccharum by Jan van der Straet, 1580-1605 (c.)(c.), Antwerp

Sugar was not just food. It was economics, politics, and culture. Merchants, craftsmen, and entire guilds built their livelihoods around its trade. Skilled workers processed imported English cloth alongside sugar, with Antwerp handling nearly two-thirds of all cloth shipped from England. From its wharves, luxury goods, spices, and, of course, sugar spread out toward France, Germany, and as far as Italy.

Sugar, Status, and the Antwerp Middle Class

Sugar fueled more than just sweets. It created a prosperous new middle class in Antwerp, unique for a time when Europe was sharply divided between nobility and the poor. This wealthy bourgeoisie had no noble titles, so they flaunted their success through clothing, houses, and, tellingly, through what appeared on their dining tables.

Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434. Depicts the elevated life of the merchant class.

Luxury tableware—spoons, salt cellars, silver knives, and glasses—became status symbols. Still-life painters like Clara Peeters immortalized these gleaming objects, often set alongside sugar loaves, cakes, and exotic foods. Gifting silverware to couples was a ritual that helped cement their social status. Even more humble craftsmen—carpenters, masons, tailors—could afford high rents, all thanks to the city’s booming sugar economy.

Still Life with Nuts, Candy and Flowers by Clara Peeters, 1611

Dinner wasn’t just nourishment. It was theater. The foods, drinks, and sugar-laden desserts served at the table provided topics of conversation and opportunities for showing refinement. Antwerp’s sugar story was not just about trade but about the extravagant lifestyles it provided to its citizens.

Still Life with Cheeses, Almonds and Pretzels by Clara Peeters, c. 1615

The Spanish Fury and Antwerp’s Decline

No golden age lasts forever. In 1576, the city suffered a catastrophe: the “Spanish Fury.” Mutinous soldiers of the Spanish Empire, unpaid and desperate, stormed Antwerp, massacring thousands of men, women, and children. Historians estimate the death toll reached as high as ten percent of the population. Geoffrey Parker even called it the “holocaust of Antwerp.”

Mutinous troops of the Army of Flanders ransack the Grote Markt during the sack of Antwerp in 1576. Engraving by Frans Hogenberg.

Merchants and artisans fled, many heading north to Amsterdam, Leiden, Haarlem, and Middelburg. With their departure, Antwerp’s dominance in sugar and trade faded. The glory days of bustling refineries, thriving arts, and wealth gave way to hardship and Spanish occupation. Amsterdam would soon rise in its place, eventually becoming the center of Northern European trade and the new capital of sugar.

From Sugarcane to Sugar Beets

Centuries later, Antwerp’s sugar story took another twist. In 1806, Napoleon Bonaparte imposed the Continental Blockade, cutting Europe off from English imports, including cane sugar. To compensate, Napoleon ordered French and Belgian farmers to cultivate sugar beets, which could be grown locally and processed into sugar.

The Entry of Napoleon into Berlin by Charles Meynier, 1810

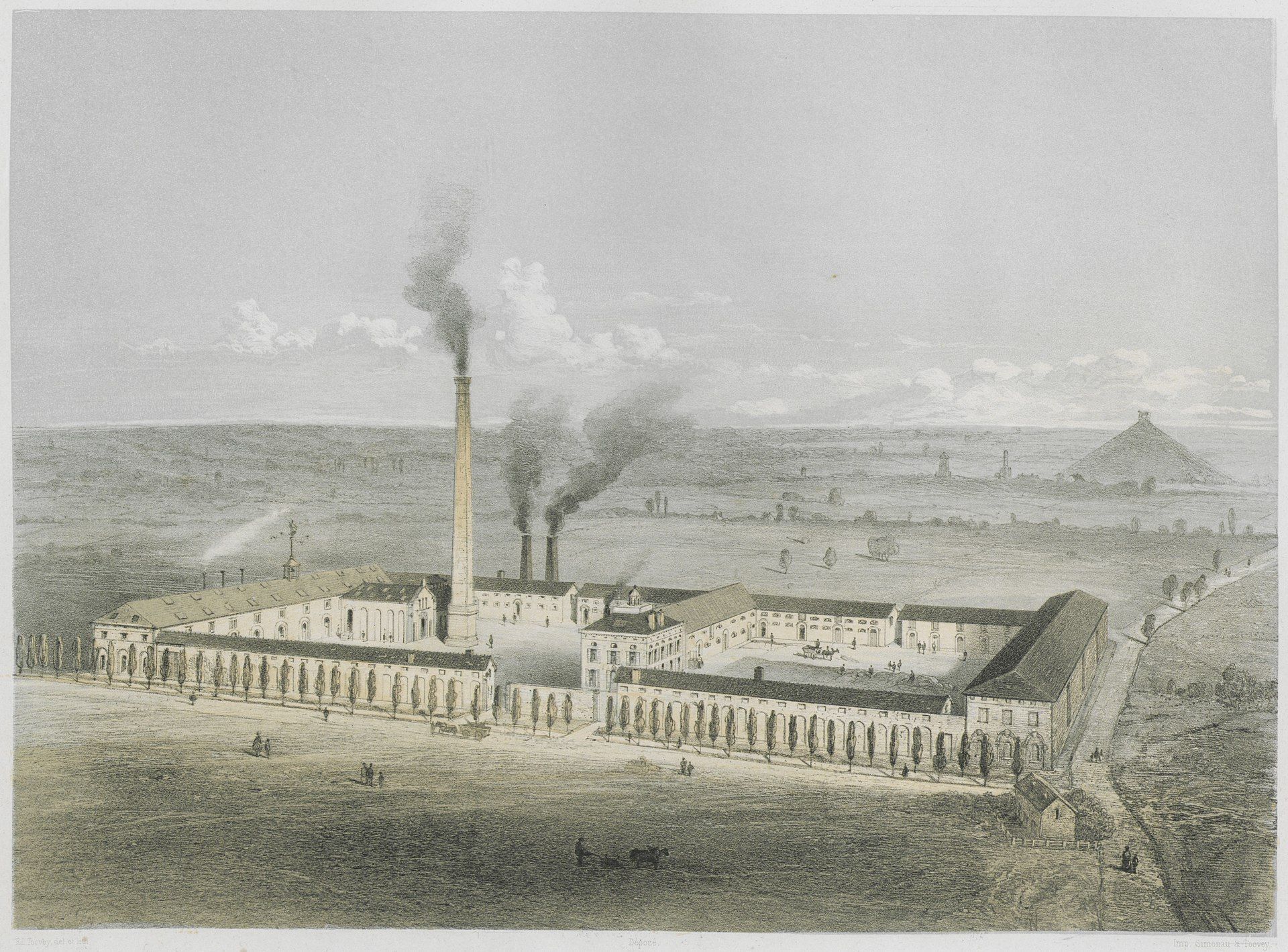

By 1812, Antwerp had fifteen sugar beet refineries. Though many refineries reverted to cane sugar once the blockade ended, protective tariffs and changing policies ensured that beets remained central to Belgian agriculture. By 1833, the number of refineries had risen again to at least fifty, though the figure quickly dropped to thirty-six a year later.

La Belgique industrielle by Edwin Toovey c. 1855

In 1843, the Belgian government introduced the suikerwet, a law that taxed cane sugar much more heavily than beet. This legislation effectively marked the collapse of the centuries-old cane sugar industry in Antwerp and ushered in the full age of beet sugar.

Brown Sugar, Kandij, and Belgian Identity

It was during this beet era that Belgium’s famous brown sugars emerged. Candico, founded in Antwerp in 1832, became a leading refinery, producing kandij (rock sugar) and stroop (syrup). The process involved slowly heating white beet sugar until crystals formed, sometimes caramelized into dark, coffee-colored syrup used on waffles and pancakes.

Another iconic sugar was cassonade Graeffe, invented in 1859 in Brussels by Karl Graeffe. Unlike other brown sugars, cassonade Graeffe is light in color with a delicate flavor, adored across Belgium as the perfect pancake topping. These sugars were not just ingredients. They became symbols of Belgian taste, tied to childhood breakfasts and national identity.

Even today, Belgians are fiercely loyal to these traditional brands. Packaging has hardly changed for generations, and families still debate the best sugar to sprinkle over their waffles. It is a living link to the past, showing how sugar moved from luxury to cultural cornerstone.

Belgian Pearl Sugar and Baking Traditions

Alongside brown sugar, Belgium is also famous for its pearl sugar—hard, crunchy nuggets that hold their shape during baking. When tucked into dough, they caramelize into sweet, golden pockets. Most famously, pearl sugar is the star of the Liège waffle (known internationally as the ‘Belgian waffle’), giving it its signature crunch and caramelized edges.

Other Belgian bakes celebrate sugar just as much. An entire cookbook could be filled with these recipes, but I will highlight a handful of them today.

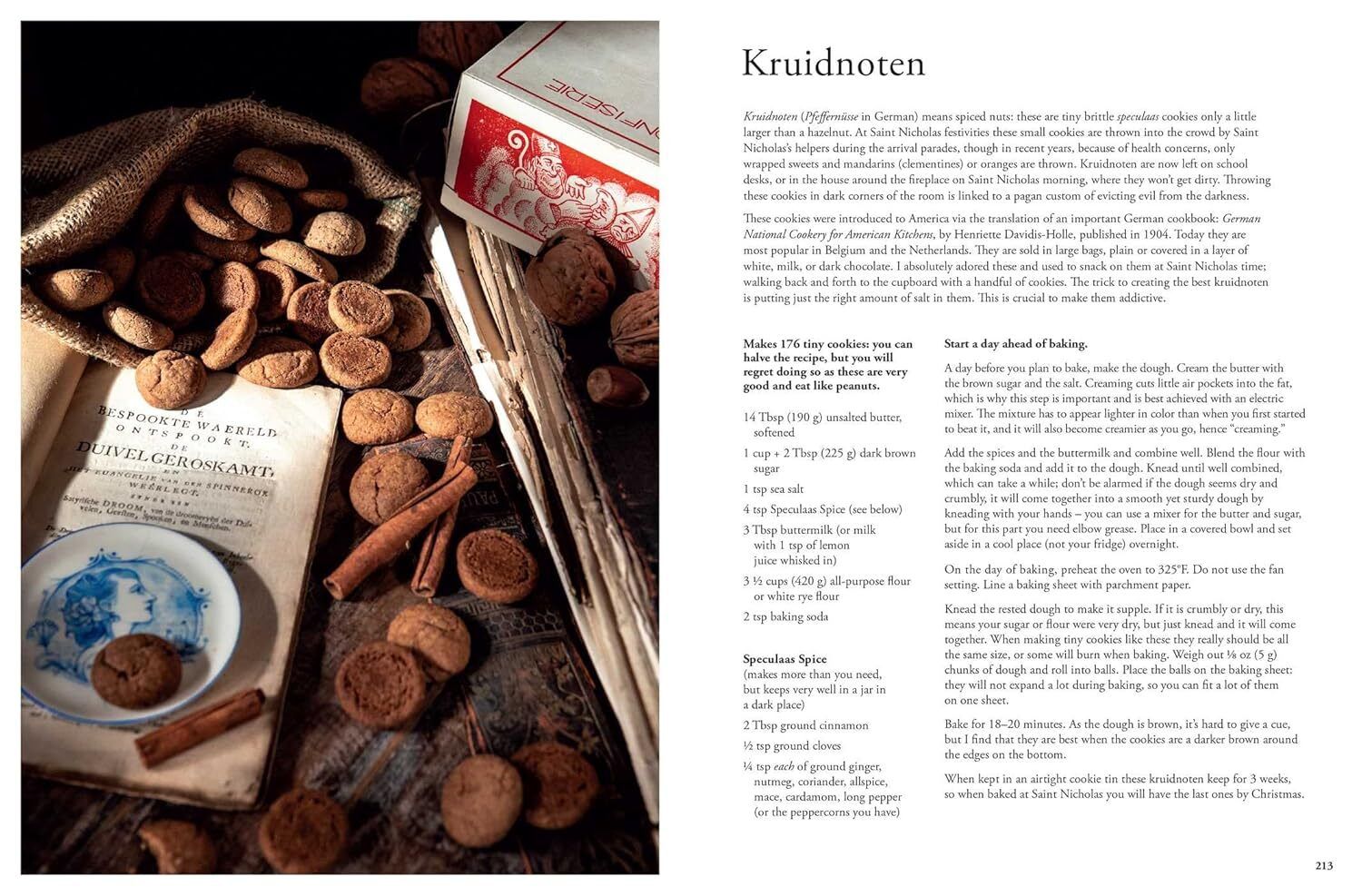

Speculoos cookies, spiced and crisp, rely on brown sugar for their depth.

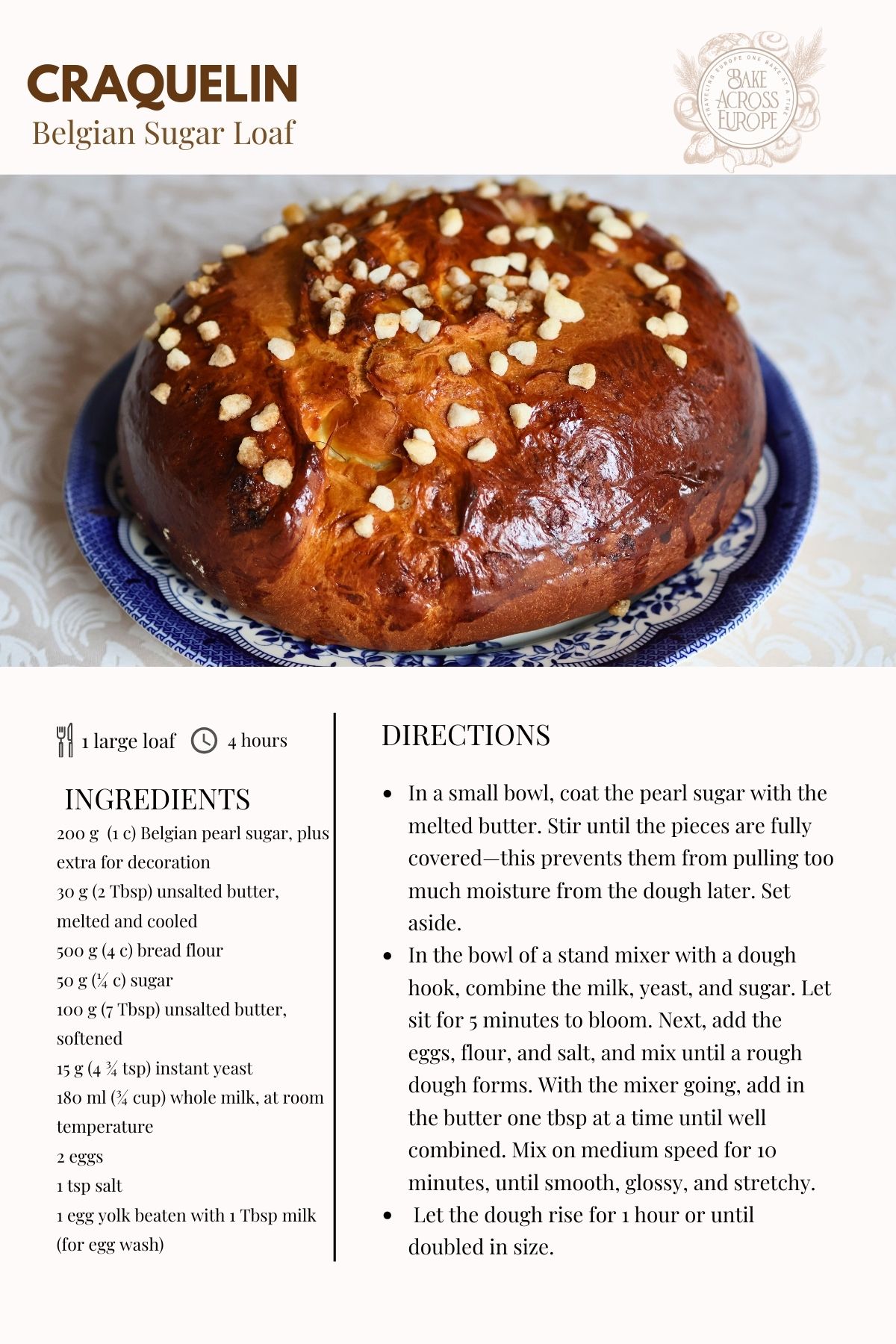

Craquelin or suikerbrood, a soft, sweet bread studded with pearl sugar.

image by Couplet Sugars

Gestreken Mastel, a spiced sweet roll cut in half, slathered with butter, sprinkled heavily with brown sugar, sandwiched together, and then ironed (using a real iron!).

image by David van Hecke

image by David van Hecke

Pain à la grecque, often mistakenly translated as Greek bread, was originally distributed to the poor by the Augustinian monastery in Brussels in 1589. The monks would bake leftover bread with sugar crystals, creating a cookie-like consistency. They are still eaten today and their name comes from the word grecht, which means city canal.

Michel Wal. CC BY-SA 3.0

Stroopwafel, a thin waffle cut and filled with stroop (sugar syrup). These are popular in both Flanders and the Netherlands. Local advice states that placing a stroopwafel over your cup of hot coffee or tea warms the stroop in the center, making them the perfect consistency for eating.

Takeaway CC BY-SA 3.0

Gaufre de Tournai are similar to stroopwafels, but instead of being filled with stroop, they’re slathered with a mixture of butter and light brown sugar.

Photo from lesfoodies.com

Oost Vlaamse Vlaai is a what I would describe as a sliceable pudding. It is made of truly Belgian ingredients, as it uses leftover peperkoek and leftover Gentse mastellen as the base and is sweetened with stroop.

image by Libelle Lekker

Tarte au sucre, or sugar tart, is made three different ways in Belgium—brown, white, or blonde, referencing the type of sugar used. This is just as the name implies, a sugar pie made with a yeasted crust.

Photo by FancyCake

And don’t forget about the Belgian sugar tart, Vaution de Verviers, that I made a video on last week. This is basically the tart version of a cinnamon roll!

Bake It Yourself

If you’re feeling inspired to bring these Belgian traditions into your own kitchen, you’ll need some special ingredients.

For authentic Belgian pearl sugar, the key to those caramel-crunchy Liège waffles and craquelin sugar bread, you can order it here. Keep in mind that Belgian pearl sugar is different than Swedish pearl sugar. The “kernel” is much larger than its Scandinavian cousin.

Dutch Stroop syrup—this one is hard to find in the US. I found it on Amazon but there isn’t a huge stock of it. There’s a lot of knock-off brands, so beware. You’re looking for sugar beet syrup, not corn syrup.

I was not able to find Belgian brown sugars on Amazon, and Belgian food suppliers like https://store.belgianshop.com/ no longer ship to the US due to the new regulations on tax duties. If you live outside the United States, however, you might peruse that website. You can find all the authentic ingredients in one spot.

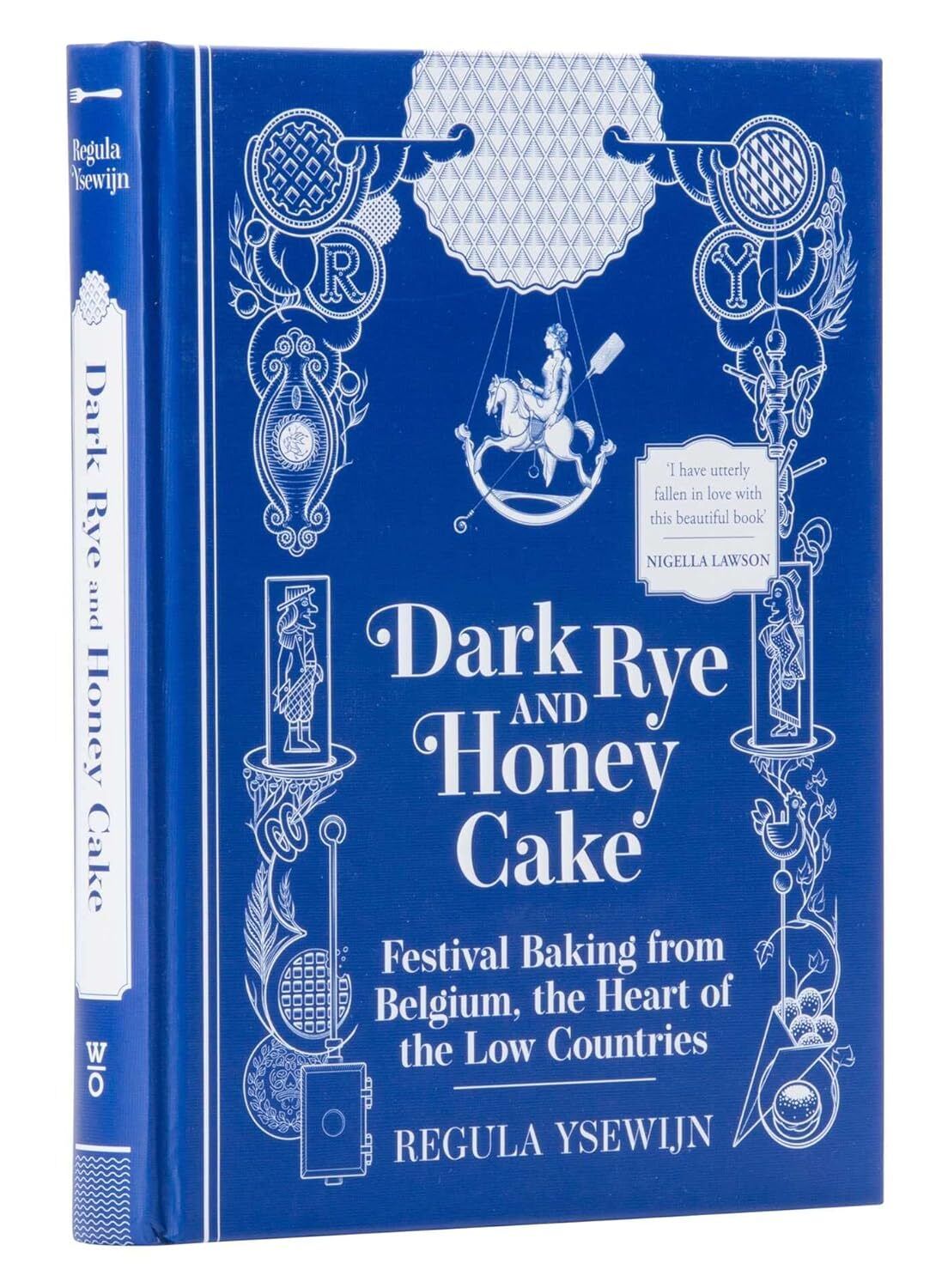

If you’d like to dive even deeper into the history and recipes of Belgium, I HIGHLY recommend Regula Ysewijn’s book Dark Rye and Honey Cake: Festival Baking from Belgium, the Heart of the Low Countries. It’s a beautiful blend of stories and bakes and I browse through its gorgeous pages often.

Closing Thoughts

Antwerp’s story shows how a simple ingredient can change the fate of a city and its culture. From the medieval myth of a giant on the Scheldt, through golden ages of sugar refining and catastrophic decline, to Napoleon’s beet revolution and the invention of cassonade Graeffe, Belgium’s history is inseparable from sugar.

And yet, that history lives on not in dusty archives but in Belgian kitchens, in every sprinkle of pearl sugar or spoonful of syrup. Baking these recipes is a way to honor the past and savor the present.

So this month, let’s bake not only for flavor but also for connection—to stories, to places, and to the sweet legacy of Antwerp and Belgium.

Recipe is printable on a web browser.

Happy baking,

Kristin